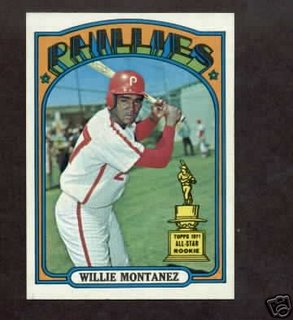

Willie Montanez

Baseball first clicked for the 8-year-old me in 1971, and it's been one of life's clicks that won't stop. That year, my uncle and grandfather started taking me to games in the Phillies' brand-spanking-new multipurpose stadium, Veterans Stadium. The future had arrived. Almost. On a terrible team of late-60s washouts and the first hint of the early-70s prospects who would grow into the franchise's lone (1980) championship team, the Phillies featured an animated rookie centerfielder, Willie Montanez, who came to the Phils as part of the compensation package for the groundbreaking Curt Flood. Despite the presence of this flashy rookie and another animated, if not immediately beloved youngster, shortstop Larry Bowa, the Phillies were in the process of extending an almost-uninterrupted 20-year stretch of losing baseball. Since losing to the Yankees in the 1950 World Series (a rare winning season for the franchise at that time, as well), the team hadn't sniffed the pennant with the exception of the legendary 1964 collapse. Of course, I was not conscious of that season's nightmare finish, but I'd been hearing about it from my uncle and grandfather as early as they began passing on their love for the game. I probably suffered psychic scars from overhearing their agony that September, when I was toddling around my grandparents' house.

Willie Montanez was a sweet-swinging, fine-fielding lefthander. My baseball mentors and I were all lefthanded. Both my uncle and grandfather were centerfielders; I was headed for two of a less-fleet lefty's options: first base and pitcher. In their own self-aggrandized image, Uncle Joe and Grandpop long valued sweet-swinging lefties, such as Stan Musial and Ted Williams as well as less-accomplished lefthanded batters from Philadelphia's past, including Johnny Callison and the Athletics' Elmer Valo. Home runs were fine, but doubles driven in the gaps and RBI are what got the men in my family stoked. En route to his 30 HR, 99 RBI, Rookie of the Year runner-up season, Montanez gave us plenty of opportunities to be stoked, but it was his style that made him one of Philadelphia's most beloved if ultimately mediocre sports heroes.

Montanez had style walking toward the plate, in the batter's box, and in the field. He had style in centerfield and at first base, his natural position, where he returned after his first 2 years in the league. Let's review his behavior at bat. Walking from the on-deck circle to the batter's box was the first of Willie's trademark behaviors: The Bat Flip. Without fail, he flipped his bat while walking toward the box. It was about as cool as it got, and like all of Willie's moves, it was done with joy and never to show up the pitcher. An important aspect of the hot-dogging Montanez is that he did it with love. He wasn't the type to stand in the box and admire home runs, he wasn't the type to glare at a pitcher, his quirky behavior was not associated with loafing or lack of concentration. Montanez was a fundamentally sound baseball player who also happened to have a great time on the field. Once through with rolling his neck and getting into his slight squat, Montanez let his swing take over. Any opportunity to react dramatically to an inside pitch or a bad swing, however, was taken. Kids across Philadelphia quickly added the Montanez batting quirks to their pick-up game repertoires alongside the Bobby Tolan high-held bat stance, the Roy White low-held bat stance, Felix Millan's ridiculous choke-up/back-scratch stance, Joe Morgan's elbow pump, and so forth.

The other Montanez trademark move was more daring and difficult to ape, even in the loosest of pickup games: The Wrist Snap. Once Montanez settled under a routine flyball or popup, a hush fell across the Vet as fans awaited the cobra-quick snap of the wrist and glove as the ball fell gently into Willie's web. Later, when Montanez moved to first base, he also did this dramatic snap, accompanied by a grand sweep of the arm, on balls rifled over to first, even balls he had to scoop out of the dirt. Now and then, if memory serves, an error resulted from one of these moves, but fans were forgiving. The Wrist Snap was too cool to deny, and Montanez was one of the league's slickest-fielding first basemen.

Yes, if you look up the sports term "hot dog" in the dictionary, the mustachioed Montanez would appear, possibly next to a shot of the even more brilliantly mustachioed and equally engaging pitcher Luis Tiant. For another view of the good-natured hot dogging of days of yore, specifically these two titans of the aluminum cart, click HERE.

About a third of the way into the 1975 season, my first baseball hero was traded even up to the San Francisco Giants for a promising yet enigmatic centerfielder, Gary Maddox. Phillies fans of what was slowly becoming a thoroughly mediocre and even hopeful team, were outraged. I'm pretty sure I cried. (Do the math - yeah, I know it's embarrassing!) By this point, Montanez had yet to come close to topping his then-recent rookie season, but he was still so cool and fun to watch. I flipped over their baseball cards, and I knew objectively that Maddox had a lot to offer. He even had a great Afro; a soulful, What's Going On-style beard; and a pretty cool stance featuring long legs that practically straddled the width of the batter's box, but he wasn't Willie. Thankfully, Gary Maddox would win over Phillies fans with his tremendous fielding, his own share of line drives in the gaps, his speed, his class, and his paralell personal odyssey through that great Phillies' team's struggle to get to and win the World Series.

Willie would move on to a number of teams, usually maintaining the sort of decent run production, good batting average, and underwhelming power that is the mark of a second-division team's first baseman. He never came close to hitting 30 HR, although he did manage to drive in 100 runs the year he moved from Philly to San Francisco with only 10 home runs (again, COOL!). Like a few other promising, sweet swingers of his era, such as John Milner and Gene Clines, he never turned out to be the second coming of one of my favorite Overlooked, Under-the-Bubble Hall of Famers, Al Oliver. The Flip and The Snap would travel with him from San Francisco to Atlanta to the Mets (god, how that killed me!) to the Pirates... He finished up his career for a few month back here, where he always belonged, where he will never be overlooked.